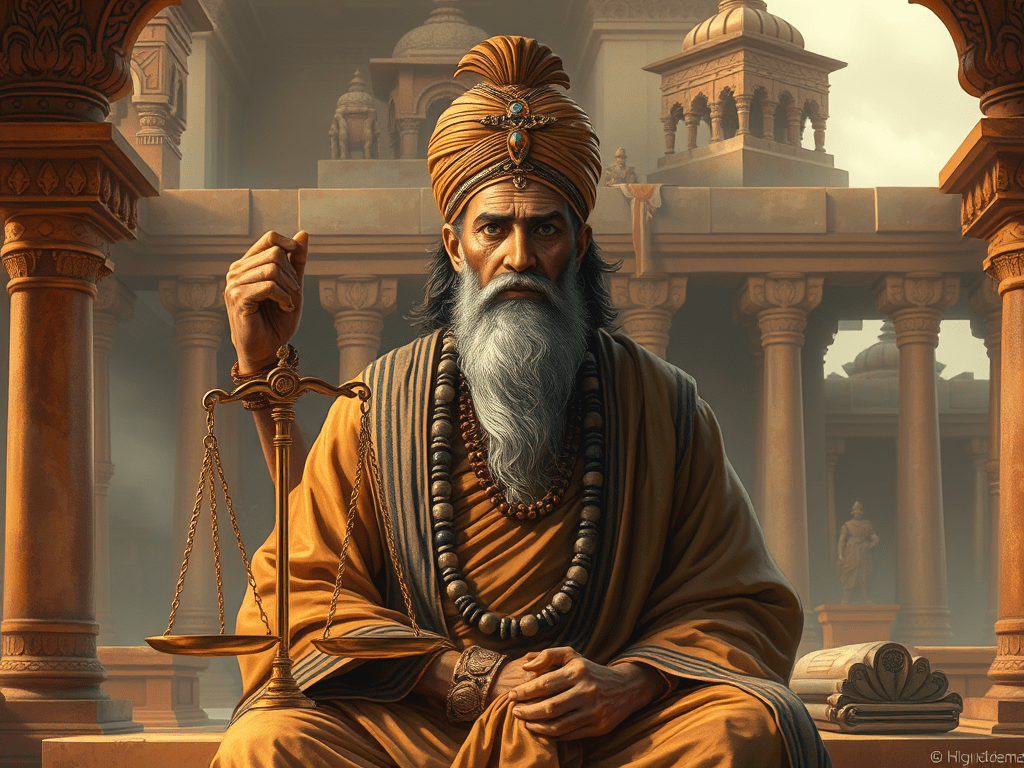

Tracing the ‘Rule of Law’ in Ancient India

9 May, 2019

“Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Lord Acton’s dictate from 1887 stands as testament, resonating the quintessential problems of administrative law pertaining to power and its exercise in civil societies since time immemorial. Administrative law is a recognised branch of law primarily concerned with the exercise of power by the executive. French philosopher Montesquieu, whilst dealing with this conundrum of exercise of power, postulated the theory of ‘separation of powers’ wherein powers of the State were vested with the triumvirate viz. the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. This classification of exercise of these powers and its checks and balances is the subject-matter of modern-day administrative law. It is through the means of this paper that the author intends to examine with the prevalence of administrative law, particularly the ‘rule of law’ in ancient Indian jurisprudence.

“Law is the command of the sovereign backed by sanction”.[1] In 1832, positivist John Austin postulated the ‘command theory’ that went on to define the concept of law in Western jurisprudence for the good part of a century. In Austinian jurisprudence, the command of the sovereign was ultimate, with the underlying presumption of ‘Rex non potest peccare’ viz. that the ‘King could do no wrong’.[2] This Austinian declaration had inherent problems in as much as the exercise of power was untrammelled and such arbitrary power could be exercised iniquitously and in a discriminatory manner. This paved the way for Englishman A.V. Dicey’s treatise concerning ‘the rule of law’ – that serves as the very basis of modern administrative law.

While expounding the fundamental attributes or tenets of the English Legal System, Dicey deals with the ‘supremacy of law’, ‘equality before law’ and a ‘judge-made constitution’ as the three fundamentals of the ‘rule of law’.[3] However, for the purposes of this paper, the author shall be restricting himself to the ‘supremacy of law’.

Dicey likens the ‘rule of law’ with the absolute supremacy or paramountcy of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power or wide-discretionary power. His arguments resonate the principle in the Magna Carta pertaining to the fact that no individual’s rights may be suspended except by due process.

“No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed nor will we go or send for him, except under a lawful judgement of his peers and by the law of the land.”[4]

Dicey critiques even the scope of discretion vested in government officials in the French system of ‘droit administratif’, in claiming that wherever there was discretion, there was room for arbitrariness.[5] He deems this as the “anathema to the British official” in the context of the administrative system in Britain.[6]

Juxtaposing the 19th Century Austinian theory with that of the 3rd Century BCE ‘Dharma Theory’ – which promulgated that the “even kings were subordinate to Dharma, to the ‘rule of law’”[7] – one might conclude that the latter is in better synergy with the modern-day notions on Administrative Law as expounded by A.V. Dicey in ‘The Law and the Constitution’. In ancient times, where ‘monarchy’ was the norm and a ‘democracy’ was but a mere aberration, the monarch (and his Council of Ministers) was the equivalent of the modern-day ‘executive’. The author shall now delve into the concept of restraint on the exercise of power of the monarch in ancient India, with specific reference to the ‘supremacy’ and ‘paramountcy’ of the law.

The ancient Indian legal literature, broadly speaking, comprised of the Vedas (Shruti), the Upanishads, Dharmashatras, Nyaya and Mimamsa (texts pertaining to ‘logic’ and ‘interpretation’) and the Puranas (the epics). The method of governance was pervasively prescribed in such literature, particularly in the Dharmashastras in the form of Rajadharmaor the ‘duties of the ruler’. Former Vice-President Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, whilst explaining the above concept, held that even kings are subordinate to dharma – ‘the rule of law’.

American political scientist Francis Fukuyama in his book – ‘The Origin of Political Order’ – traces the history of the concept of a State from its’ very inception. After dealing with Chinese Tribalism, Fukuyama refers to the then prevailing position in ancient India. After examining the varnas and jatis as they had existed, he noted how the inextricably linked law and religion, laid foundation to a system that he describes as the ‘rule of law’.[8] The essence of this ‘rule of law’ is a body of rules that reflected the community’s sense of justice that is higher than the wishes of the person who acts as the monarch. The laws themselves were created not by the monarch but by a class of educated scholars i.e. brahmins through an interpretation of a “higher norm” as prevalent in the shastras. The laws expressly declare that the varnas are not meant to serve the monarch nor are their rights in any way subordinate or second to his. Rather, it is the monarch who must be the protector of citizen’s rights in order to gain legitimacy.[9] A passage from the Hindu epic Mahabharata explicitly sanctions a revolt against a monarch in breach of his Rajadharma – the ballad of tyrant King Vena, who was assassinated by sages for banning inter-caste marriages and forbidding all sacrifices except to himself, is testament to this fact.

Manu – renowned for being the pioneer of promulgating law – in his commentary the Manusmriti, maintains that the ‘locus of sovereignty’ lay in the law and not in the monarch.

“The law (danda) is the ruler the person with authority, the person who keeps the order of the realm and gives leadership to it.”[10]

While Fukuyama referred to the existence of a “higher norm” in the governance of the Indian subcontinent at the time of political order in the world, the word “higher norm” or ‘dharma’ in itself was left undefined and unexplained by him. Therefore, at this conjecture, it is imperative to delve into the meaning of the word ‘Dharma’ and what it entails.

In his famous treatise – ‘The Legal and Constitutional History of India’ – Justice M. Rama Jois whilst defining the character of law explains the overarching principle of the ‘rule of law’. He explains that ancient Indians recognised law as an instrument for upholding the rights and liberties of individuals. The weak or the injured could seek protection of law from the king. The king or State could enforce the law by imposing a sanction for which he was empowered.[11]

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, having recognised the power of the king to impose sanctions proceeds to declare that Dharma viz. the law, is superior to that of the King. The ‘dharma’ was created to enable the King to protect his peoples. The Upanishad ordains as under:

“The law is the king of kings,

Nothing is superior to the law.

Law aided by the power of the king,

Enables the weak to prevail over the strong.”[12]

There are a large number of principles in classical Hindu Law that prescribe the ‘righteous conduct’ to be followed, especially by the ruler. These principles are referred to as the ‘dharma’. As is evident from multiple texts, Dharma has always been declared as higher to the ruler to whose declaration he is bound by. The concept of dharma is therefore much larger than the principle of the ‘rule of law’ in its present form. The the maxim ‘Rex non potest peccare’ viz. ‘the crown could do no wrong’ never applied to ancient India. In fact, the Manusmriti even prescribed a proportionally higher punishment for the monarch, holding them liable for any crime or misdemeanour.

“The king himself is also liable to be punished for an offence, with one-thousand times more penalty than what would be inflicted on any other citizen”[13]

[1] The Concept of Law, John Austin

[2] Herbert Broom, A Collection of Legal Maxims, Classified and Illustrated, 23 (London, A. Maxwell and Son 1845).

[3] A.V. Dicey, ‘The Law and the Constitution’ (1915), 56.

[4] The Magna Carta, British Archives, <http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/magna_carta/>.

[5] A.V. Dicey, ‘The Law and the Constitution’ (1915) 202.

[6] Wade & Forsyth, ‘Administrative Law’ (2009) 17-21, 286-287.

[7] Manu, ‘Manusmiriti’, Chapter XVII, Section 22.

[8] Francis Fukuyama, ‘The Origins of Political Order’, (2011), pg.173.

[9] Kranti Sharma, ‘Aspects of Political Ideas’, (1984) pg.159-60.

[10] Manu, ‘Manusmiriti’, Chapter XVII, Section 7.

[11] Justice M. Rama Jois, ‘The Legal and Constitutional History of India’, Volume I, Chapter 3, pg. 52.

[12] Yajnavalkya, ‘Brihadaranyaka Upanishad’, Part 1, Chapter 4 Verse 14 (SBE Volume XVI), 89/14.

[13] Manu, ‘Manusmiriti’, Chapter XVIII, Section 366.

Leave a comment