October 5, 2019

It is the 21st Century and the ‘digital age’ has dawned on us as we edge towards the ‘Internet of Things’ . Every minute, over two-hundred million e-mails are communicated globally, more than seven million photos are shared, and two million eight hundred thousand people react to posts on a plethora of social media platforms across the world. The hyper-connected world is now. A network of increasingly invasive devices – our mobile phone companies, the apps and websites we visit and even the Government – map and record our data. The world has now begun to know more about individuals more through the data collected about them rather than interpersonal interactions. The day isn’t distant when our digital shadow is compromised and “we soon become less valuable than the data we produce.”[1]

In such a day and age where the world has fully stepped into the digital era, citizens around the globe have found their current lives and past becoming less private by the day. The internet is designed to store everything that was ever uploaded on its servers and the transmission of this information has been reduced to nanoseconds. The strength of the internet is however, also its weakness. Information that is false or the contents of which are not meant to for the public eye may just as instantaneously be transmitted to the world and would be inconsistent with the

‘right to privacy’. Aristotle is often quoted with the saying, “Man is by nature a social animal” and the free accessibility of such negative information might be damaging to a person’s reputation. The importance of a person’s reputation has been highlighted in many judgements by the judiciary including in Gian Kaur[2] and the criminal defamation case[3] wherein the Courts have accepted arguments that reputation is tantamount to life and is a natural and inalienable right. Even the incumbent Chief Justice remarked on the same “when reputation is hurt, a man is half-dead … It is dear to life and on some occasions, it is dearer than life… become an inseparable facet of Article 21 of the Constitution.”[4]

In such a scenario where ‘reputation’ has been held very highly by the judiciary, there may be instances, where one wishes to hide from public domain information that is irrelevant, not meant for public knowledge or even false that is available freely online. This desire for invisibility from the public eye has emerged as the ‘right to be forgotten’.[5] The right encompasses the citizens’ rights to approach intermediaries, websites, search engines and social platforms and demand the erasure of certain information regarding them.[6]

The ‘Right to be forgotten’ in essence, arose from the desires of individuals to “determine the development of their life in an autonomous way, without being perpetually or periodically stigmatized as a consequence of a specific action performed in the past.”7

In 2014, the right came into limelight when the European Court of Justice began hearing the submission in the Google Spain Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja González case.[7] The petitioner Mario Costeja González sought the removal of information regarding the past forced sale of his property on the grounds of it being irrelevant and out of date. The Advocate General and Google both contended that the ‘right of the general public to freedom of information’ takes precedence over the ‘right to erasure’ of an individual.

The European Court of Justice in this landmark judgement opined that an internet search engine operator is responsible for the processing of data that appears on the web pages published by third parties.

They permitted the petitioner – González’s – plea of removal of the data with the caveat that it may be permissible only when such information becomes “unnecessary and inadequate

regarding the purpose it was collected for.”[8] The implied purpose test was thus created, on the satisfaction of which, the plea of erasure can be maintained.10 For instance, if a person’s name is searched, a string of results displaying links to various web pages containing further information is generated by the search engine operator. Persons aggrieved due to such display of certain information may directly approach operators and have the right to proceed against the intermediaries in case of denial of such services.

Furthermore, this has been incorporated in the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) under Article 17 that grants expressly to the citizens the ‘Right to Erasure’ (Right to be Forgotten’) with certain stipulations.

Although the European Court of Justice has sanctioned this right, the status of the ‘right to be forgotten’ in the world continues to be largely divided. Many European nations recognise this right in terms of the French Principle of ‘le droit i l’oubl’I’ or the ‘right of oblivion’[9] wherein a criminal having rehabilitated can object to the publication of facts of his or her conviction.[10] Canada also espouses a similar view wherein individuals may request search engines to remove offensive information about them.[11] Countries like Japan deny the granting of such right on the grounds of public interest.[12]

The recent judgement of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India and Ors.[13] expressly granted to the citizens of India, the fundamental ‘right to privacy’. It is interesting to note that India does not expressly recognise the ‘Right to be Forgotten’ or for that matter, have a statute explicitly elucidating the ‘Right to Privacy’ to at least help the facilitation of interpreting the former in terms of the latter. Nonetheless, Indian Courts have prior to this interpreted the ‘right to privacy’ as a “subset of personal liberty”[14], “right to be let alone”[15] [16] and that freedoms and rights in Part III could be addressed by more than one provision.19 [17]

On the issue of ‘Right to be forgotten’, the Courts have trodden on both paths with the Gujarat High Court having dismissed it and the Kerala High Court and Karnataka High Court having entertained requests for erasure of information on the internet in the past.

The petitioners in the case of Dharamraj Bhanushankar Dave v. State of Gujarat[18] sought the removal of a URL containing a ‘non-reportable judgement’ that was hosted by the legal website IndiaKanoon.com and showed on Google Search. He contended that the publication was violative of Article 21 of the Constitution and had adversely affected his personal and professional life. The High Court of Gujarat however observed that “mere publication on the website is not tantamount to reporting” and that there was no violation of the petitioner’s fundamental right to life with dignity.[19]

The High Court of Kerala however took an approach alternate to the Gujarat High Court in a recent judgment23 – following the Puttaswamy[20] judgement guaranteeing the ‘right to privacy’ – wherein it ruled in favour of a rape victim who alleged that such publication of information had “caused disrepute, mental agony, distress, pain and suffering and loss of earnings to her”.

The Court passed an interim order to the intermediaries for the removal of the victim’s name with concurrence to the guidelines established in the Gurmit Singh[21] and Putta Raja[22] judgements.

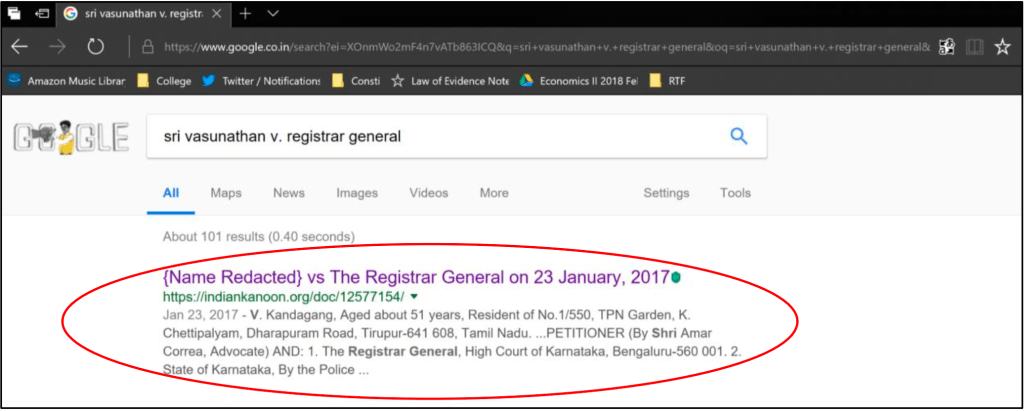

The Karnataka High Court in Sri Vasunathan v. The Registrar General[23], (subsequently altered to read {Name Redacted} v. The Registrar General) wherein the petitioner – another victim of rape – sought the removal of her name from case-titles of orders by the Courts in a prior case citing that this negatively affected her reputation and social life. The Court took an approach in line with the European Union’s Courts rulings where the ‘Right to be Erasure’ was granted in cases deemed to be highly sensitive to victims of rape and non-consensual pornography

(otherwise known as revenge porn) which adversely affected “the modesty and reputation of the concerned persons.”

The Karnataka High Court’s reference to the ruling being in concurrence with the notion of the ‘Right to Erasure’[25]bestowed upon citizens belonging from the European Union might, more or less, be interpreted as an implied green signal towards the incorporation of the ‘Right to be Forgotten’ in India. The right continues gathering recognition in the form of Court orders granting the taking down on request of information deemed to be violative of the right to privacy bestowed upon citizens.

The Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF) – an organisation emanating from the #SaveTheInternet initiative – recently secured with consent from the High Court of Delhi, a legal intervention demanding the recognition of ‘The right to be forgotten’.[26] This case of Laksh Vir Singh Yadav v. Union of India and Ors.[27] is still being heard by the High Court and it would be interesting to see whether the ‘right to privacy’ of an individual is given precedence over the general public’s ‘right to information’ in this clash of individual and group rights.[28] The Courts must assess whether the Indian Constitution’s guarantee of the fundamental right to life and liberty under Article 21 — which many understand to include a right to privacy — encompasses a right to forget or de-list information. In what would in all likeness be a landmark judgement, free internet activists, legal scholars and legislators among the thousands of victims eagerly await to see how this emerging concept will be developed and statutorily framed by the judiciary.

While thousands await the ruling in the Laksh Vir Singh Yadav case for the implementation of a statute expressly elucidating regulation pertaining the ‘right to be forgotten’ and its stipulations as to where and how it may be utilised, what has been largely left untouched is an analysis of the Puttaswamy judgement[29] in terms of it guaranteeing implicitly a ‘right to be forgotten’.

Justice Chandrachud, writing for three other judges, opened the judgement. In the second paragraph of the judgement itself, he remarked that:

“Privacy, in its simplest sense, allows each human being to be left alone in a core which is inviolable. Yet the autonomy of the individual is conditioned by her relationships with the rest of society … The overarching presence of state and nonstate entities regulates aspects of social existence which bear upon the freedom of the individual.”

It is here that one can gather how he interlinks society to the individual in terms of privacy.

He further uses quotes be renowned philosophers including J.S. Mill, John Austin, John Locke and Thomas Cooley while undertaking a dynamic approach to the constitution to explain the notion of privacy. He even stresses upon the issue of how the Constituent Assembly’s dismissal of the same should not be taken as a ‘black letter’ and explains how the Constitution is a living document that has evolved over time with understanding and how it shall continue to do so with subsequent generations.

Chandrachud further lays claim that with this non-originalist interpretation of the law that

“the right to privacy is an element of human dignity and that the sanctity of privacy lies in its functional relationship with dignity and by securing the inner recesses of the human personality from unwanted intrusion.Privacy recognises the autonomy of the individual and the right of every person to make essential choices which affect the course of life.”

One can logically deduce from this that the ‘right to be forgotten’ may be implied from such an explanation of the relationship between privacy and dignity. It was earlier mentioned in this paper that the Courts value dignity and reputation very highly. If there is certain information about a person that is as mentioned previously irrelevant, not meant for public knowledge or even false that is available freely online for every person in the world to see, this would in all circumstances be damaging to the reputation of such person. The ‘privacy’ Justice

Chandrachud talks about in this context stresses upon the autonomy of individuals and protection from unwanted intrusion and seems to satisfy all the ingredients of the ‘right to be forgotten.’

Following the footsteps of his peer Chandrachud J., Justice Abhay Mohan Sapre also engages with a dynamic interpretation of the Constitution with references and interpretation to the preamble in particular. The interpretation of ‘the right to be forgotten’ as understood from Justice Chandrachud’s analysis proves useful in deconstructing Justice Sapre’s interpretation of the word ‘life’ and his understanding of intertwinement of ‘the unity of the nation’ with respect to the ‘dignity of an individual’ – and how he questions the existence of the former when the latter is in breach. Thus, it can be understood from Justice Sapre’s judgement that the ‘Right to privacy’ embodied the ‘Right to be forgotten’.

Among the nine-judge bench, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul’s concurring opinion affirmed the cases’ ratio. He predominantly spoke about how the right to privacy is not merely a common law right but a fundamental right. He further identified ‘the right to be forgotten’ – the presence of which may be found in physical and virtual spaces such as the internet and under the umbrella of informational privacy. Recognising that people may make mistakes in the past which should not be held against them through the digital footprint left behind, Justice

Kaul seeks to bolster the ability of the right to privacy to nurture the ability to evolve.[30]

This right in his opinion, puts individuals in control of the information transmitted and communicated and grants the right to seek erasure of data concerning them. He remarked that:

“The right of an individual to exercise control over his personal data and to be able to control his/her own life would also encompass his right to control his existence on the Internet”.

Although he places certain restrictions on when the right may be availed, his reasoning conflicts with the ‘Right to Information’ and due to this it could also be interpreted as the public not having a claim to the access of truthful information.

That being said, at present the right to be forgotten exists merely in the nascent form and its enforceability is limited to a case-by-case basis both in the Court and when in dealing with the requests made to intermediaries.

As India awaits legislation pertaining to data protection, those advocating the right to be forgotten must acknowledge the hurdles in its path. The mere pronouncement of a fundamental right to privacy does not resolve them.

[1] Ubisoft Co., ‘Watch_Dogs 2 E3 Release’< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qs4OcQNOM34&t=50s> accessed 28 April 2018

[2] Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab (1996) 2 SCC 648.

[3] Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India W.P. (Crl) 184 of 2014.

[4] Om Prakash Chautala v. Kanwar Bhan and Ors (2014) 5 SCC 417.

[5] Claire Overman, ‘The Right to be Forgotten European Reactions: Part I’ <http://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/the-right-tobe-forgotten-european-reactions-part-1/> accessed 27 April 2018.

[6] Vikrant Rana, ‘Will Judiciary Recognize the Emerging “Right to be Forgotten?’ <www.mondaq.com/india/x/ 5782 62/data+protection/Will+Judiciary+Recognize+The+Emerging+Right+To+Be+Forgotten> accessed 15 April 2018. 7 Alessandro Mantelero, ‘The EU Proposal for a General Data Protection Regulation and the roots of the right to be forgotten’ <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0267364913000654?via%3Dihub> accessed 13 April 2018.

[7] Google Spain SL, Google Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos, Mario Costeja González C-131/12 ECLI:EU:C:2014:317.

[8] ibid 10 Swapnil Tripathi, ‘India and its version of the Right to be Forgotten’

<http://www.sociolegalreview.com/india-and-its-version-of-the-right-to-be-forgotten/> accessed 22 April 2018.

[9] Lucie Ranfont, ‘Right to oblivion: the CNIL and Google agree before the Council of State’

<www.lefigaro.fr/secteur/high-tech/2017/02/03/32001-20170203ARTFIG00267-droit-a-l-oubli-la-cnil-etgoogle-s-accordent-devant-le-conseil-d-etat.php> accessed 26 April 2018.

[10] Emile Laporte, ‘What is the right to oblivion?’ <https://openclassrooms.com/courses/controlez-l-utilisationde-vos-donnees-personnelles-1/qu-est-ce-que-le-droit-a-l-oubli> accessed 26 April 2018.

[11] A.T. v. Globe24h.com 2017 F.C. 114 (Canada).

[12] DLA Piper, ‘The only exception to the rule is when the private interests supersede the public interest’ <http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=37824d3f-3401-4285-8641-8a1ced989cab> accessed 26 April 2018.

[13] Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India and Ors W.P.(C) NO.000372/2017.

[14] A K Gopalan v. State of Madras 1950 SCR 88.

[15] R. Rajagopal v. State of T.N (1994) 6 SCC 632.

[16] People’s Union for Civil Liberties v Union of India AIR 1997 1 SCC 301. 19 R C Cooper v. Union of India 1970 SCR (3) 530.

[17] Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India 1978 SCR (2) 621.

[18] Dharamraj Bhanushankar Dave v. State of Gujarat SCA No. 1854 of 2015.

[19] ‘A series of right to be forgotten cases in courts highlight how India doesn’t have a privacy law’ < https://scroll.in/article/831258/a-series-of-right-to-forgotten-cases-in-courts-highlight-how-india-still-doesnthave-a-privacy-law> accessed 31 March 2018 23 *Civil Writ Petition No. 9478 of 2018.

[20] Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India and Ors W.P.(C) NO.000372/2017.

[21] State of Punjab vs Gurmit Singh, 1996 AIR 1393.

[22] State of Karnataka v. Puttaraja, AIR2004SC433.

[23] Sri Vasunathan v. The Registrar General W.P. No. 62038/2016

*The Courts have prohibited the publication of the names of the parties.

[24] ‘Google Search subsequent to the ruling’

<https://www.google.co.in/search?ei=QGfnWsicJorsvgSzqJvoCA&q=sri+vasunathan+v%2C+registrar+general

&oq=sri+vasunathan+v%2C+registrar+general&gs_l=psyab.3…24665.28524.0.28769.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0..0.0….0…1.1.64.psy-ab..0.0.0….0.6OUoFhv3OPM> accessed 23 April 2018.

[25] Article 17 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

[26] ‘Delhi HC accepts intervention against a Right to be Forgotten case in India’

<https://www.medianama.com/2016/09/223-delhi-hc-right-to-be-forgotten/> accessed 25 April 2018

[27] Laksh Vir Singh Yadav v Union of India and Ors., WP(C)1021/2016 (Del).

[28] ‘Does the Right to Privacy Include the Right to be Forgotten?’

<http://indiatoday.intoday.in/technology/story/does-right-to-privacy-include-right-to-be-forgotten-delhi-hc-asksgoogle/1/656798.html> accessed 3 April 2018

[29] Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India and Ors W.P.(C) NO.000372/2017.

[30] Sohini Chatterjee, ‘In India’s Right to Privacy, a Glimpse of a Right to be Forgotten’

<https://thewire.in/law/right-to-privacy-a-glimpse-of-a-right-to-be-forgotten> accessed 28 April 2018

Leave a comment